The economics of childcare are complicated, to say the least. While providers barely make a profit, parents are paying an arm and a leg to send their children to daycare.

This is due to one reason — childcare is a labor-intensive industry.

Taking care of children requires a large number of people. So, providers use most of their revenue for payroll expenses, meaning less profits. At the same time, those payroll expenses are divided among several workers, leading to low wages. Since providers do not have access to many cost-reducing mechanisms, parents must always pay high and rising costs for childcare.

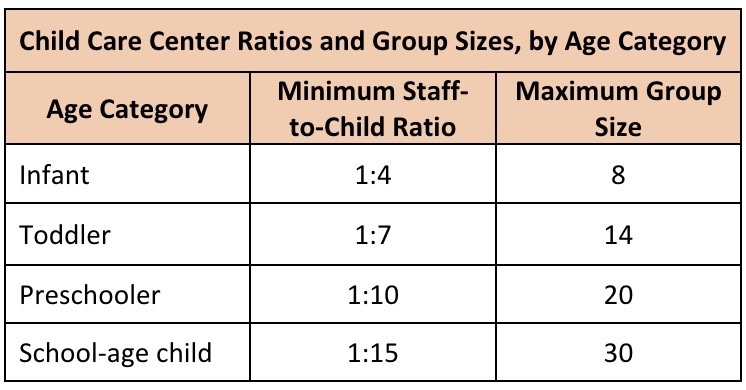

This is worse for younger children such as infants. Since infants require more workers than older children, they are more expensive to care for and, therefore, more costly for parents. In Minnesota, for example, state law requires that licensed daycare centers provide 1 teacher per 4 infants. For toddlers, the ratio is 1 to 7 and for 4-year-olds, the ratio is 1 to 10.

Table 1: Minimum Staff-Child Ratios for Lincensed Center-Based Care

Due to the high cost of caring for infants, providers rarely make money on young children. In fact, according to some surveys, providers make losses on infants and can break even on toddlers. Providers make profits on pre-schoolers, which they can use to subsidize infants.

To put it briefly, the revenue from older children is crucial to keeping childcare providers in business. This business model, however, is under threat and the culprit, unsurprisingly, is government action.

Expanding Pre-K is hurting private providers

In Minnesota, efforts are underway to expand the provision of free — more accurately publicly funded — Pre-K. Last year, for example, in addition to increasing spending on the Childcare Assistance Program (CCAP), lawmakers also expanded the number of slots available under the Voluntary Pre-K program in Minnesota by over 5,000 slots.

This means that older children who would otherwise go to a private provider will be pulled into the public pre-k system leaving only infants and toddlers, who are costly and unprofitable to care for, which could become detrimental to the private childcare market.

In a Survey conducted in March by Children’s First Finance and the Minneapolis Fed, for example, providers expressed concern at the growing number of older children who during the pandemic

were increasingly cared for by parents working from home or by early learning programs at public schools. Many providers said their business became more dependent on the care of infants and toddlers, the least profitable age groups.

A northeastern family childcare provider had the following to say about public schools.

They take most my desired age group leaving only infants and toddlers looking for care. And since we are limited on the number of infants and toddlers, it impacts my income and will eventually put me out of business altogether.

Surely, one can argue that there are tangible benefits to providing “free” Pre-K to parents. But like everything else with policy, that comes with tradeoffs.

In this case, in addition to the burden placed on taxpayers, offering free Pre-K programs could drive private providers out of the market, worsening childcare shortages and leading to even higher prices, especially for infants and toddlers. This has already been observed in New York City, where according to one Working paper, free Pre-K expansion resulted in 2,700 fewer childcare slots for infants in the private market. Worse yet, this effect occurred entirely in high-poverty areas.